In March 2023, the European Central Bank (ECB) published its first climate-related disclosures on corporate asset purchases. The report shows the bank’s portfolio is yet to decarbonize at a pace that matches European climate goals. More importantly, it does not provide any information to make it possible to assess the central bank’s support for companies with emissions and practices at odds with these goals. If it intends to stay aligned with its climate roadmap announced in 2021, the ECB should both exclude fossil fuel developers and extend its climate approach to the stock of corporate bonds.

On March 23rd, the European Central Bank (ECB) published the Climate-related financial disclosures of the Eurosystem’s corporate sector holdings for monetary policy purposes. These first disclosures were part of the central bank’s ‘climate roadmap’ adopted in 2021. They aim to give insight into the climate impact of its purchases of corporate sector assets through the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) and the corporate sector purchase programme (CSPP). The disclosures do not cover the climate impact of any other monetary operations.

Carbon metrics: Nothing much to see

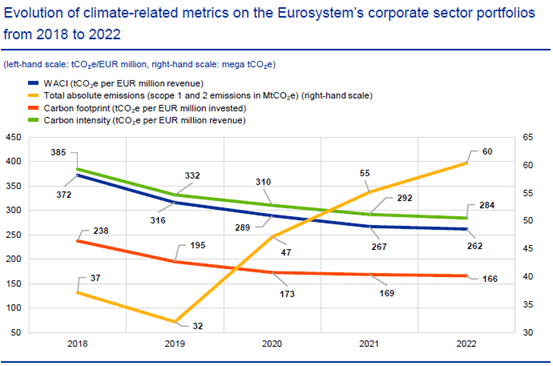

In its report, the ECB focuses on four metrics:

- Total carbon emissions the ECB theoretically contributed to by buying corporate assets;

- Carbon footprint, which adjusts total carbon emissions considering the size of the portfolio;

- Carbon intensity, which measures the carbon emitted by the companies financed in relation to their revenues;

- Weighted average carbon intensity (WACI), which considers carbon intensity given the weight of each corporation in the ECB’s portfolio.

On the one hand, WACI and carbon intensity give an indication of the carbon efficiency of the corporations financed by the ECB. On the other, total carbon emissions and carbon footprint focus on the amount of carbon emissions the ECB’s corporate portfolios is responsible for, regardless of corporations’ carbon efficiency. None of the carbon metrics consider scope 3 emissions from the companies financed.

Source: ECB

The evolution of the four metrics over the past few years reveals two trends. First, the increase in CSPP and introduction of PEPP in 2019 have led to a significant rise in total carbon emissions (circa 88% increase between 2018 and 2022). Second, there is not enough of a decline in the other carbon metrics. Between 2019 and 2022, based on a constant portfolio size, the ECB only decreased its contribution to carbon emissions by 29 tCO2e per EUR million invested (circa 15% decrease total, and 5% average annual decrease). Regarding average carbon intensity, the situation is similar with the decrease in WACI reducing over time to almost reach a standstill between 2021 and 2022 (2% decrease). Therefore, the ECB has been responsible for more carbon emissions in absolute terms in the last few years, and also nearly stopped improving its portfolios’ carbon efficiency.

Furthermore, in its disclosures, the ECB suggests that the carbon intensity improvements of its portfolios were primarily driven by companies in the various sectors developing better practices rather than an active policy of the ECB to select more efficient issuers (1). The ECB only started incorporating climate considerations into corporate bond purchases in October 2022 by tilting its reinvestments towards issuers with a better climate performance (2). Therefore, the trends seen in the report are merely a passive feature.

Missing the point?

The climate-related disclosures overall fail to provide meaningful information on the impact of the companies supported by the CSPP and PEPP. Despite past studies – including from the ECB itself – showing a carbon-bias in corporate asset purchases (3), the ECB provides no information on the sectoral evolution of the portfolio or on the inclusion of carbon intensive issuers such as fossil fuel companies. This is even more problematic given that the PEPP increased the ECB’s support to all five oil and gas majors between April 2020 and September 2021 (4), and the ECB’s ‘climate tilting’ framework does not exclude them from upcoming purchases.

As ECB board members acknowledged, the recent tilting of the portfolio cannot achieve the necessary reduction due to the large stock of existing holdings vis-à-vis reinvestments (5), and to the monetary tightening that diminishes the size of reinvestments. A rapid change in the portfolio would be needed to boost decarbonization. The only way to operate that shift is to start looking at the stock of assets.

To conclude, the ECB must update its approach to reach its commitment to decarbonize its corporate asset purchases by: a) Extending its climate approach to tilt the stock of corporate assets held towards corporations with better climate performance; b) Updating its climate approach to exclude companies at odds with the 1.5°C objective, notably fossil fuel developers. These two recommendations alone would not be enough for the ECB to fully integrate climate considerations in its monetary policies, in line with its mandates (6). Indeed, the ECB must consider other levers across its monetary policies, from setting up green lending facilities to decarbonizing its collateral framework (7).