On Wednesday 24th November, the Transition Pathway Initiative (TPI), a global asset-owner led initiative which aims to assess companies’ preparedness for the transition to a low-carbon economy, published an update of its energy sector assessment. Their new benchmark comes to a very surprising conclusion, one that is both too good to be true and technically impossible. According to the TPI, three oil and gas majors and a further eleven electric utilities are 1.5°C-aligned, including RWE, TotalEnergies, and Eni. This analysis contains major biases, while, ironically, the TPI also misunderstands the very concept of “transition pathway”. Investors intent on meeting their climate commitments should eschew this analysis, which would see them investing in major polluters, at the cost of their credibility on these issues.

The TPI aims to assess which companies are aligned with climate requirements, to help climate-conscious investors direct their investment in the most responsible way. As more and more financial institutions are making room in their fossil fuel policies to keep investing in companies compatible with 1.5°C aligned pathways, these kinds of benchmarks are likely to impact investment decisions. Given the major business and investment decisions at stake, the methodology and the data used by such benchmarks are of great importance. And in this case, something has certainly gone awry with both TPI’s approach and data (1).

TPI missing the mark

To figure out whether a company is aligned on a given scenario, the TPI uses energy-economic models with climate inputs to allocate carbon quotas to different economic sectors, year by year. These carbon quotas are then used with forecasts of activity of these sectors, to calculate sector-wide emission intensity pathways. Finally, the TPI compares the pathway of the relevant sector to the targets provided by the companies listed in the benchmark.

What’s wrong with the TPI’s approach? The benchmark’s “carbon performance” analysis solely relies on declarations from companies and does not consider facts and figures. This means that even if companies put forward unrealistic ambitions, the TPI benchmark will build on it anyway. TPI researcher Nikolaus Hastreiter states this very clearly: the feasibility of the climate ambitions “is not something we’re looking at the moment. That would require assessing, for example, the capital expenditure plans of companies, and the disclosure of companies is really not advanced enough at this point”.

As for its “management quality” scoring, the TPI misses an essential point: mitigation targets for scope 3 emissions. Indeed, TPI does ask the companies whether they disclose scope 3 emission but does not ask about scope 3 targets. This is problematic given that scope 3 emissions account for a significant share of emissions in sectors like the transport and oil and gas: in 2020, scope 3 emissions of TotalEnergies made up almost 90% of the major’s total emissions. Scoring the company’s transition management while omitting most of what needs to be addressed is like throwing a bucket of water on a forest fire.

A major oversight: short-term emission cuts

According to the benchmark, companies like TotalEnergies, ENI and RWE are aligned “over the long-term”, by 2050. However, TPI’s approach disregards the critical importance of short and medium term emission reduction to avoid immediate acceleration of climate change. It’s worth remembering that transition pathways exist for a reason. By setting year on year targets covering 2021 – 2050, they act as a guide to achieve that climate goal in a controlled/phased and socially and economically acceptable manner.

Climate scientists have made clear that reaching carbon neutrality by 2050 under a 1.5°C pathway requires drastic and immediate cuts in global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The UNEP Production gap report calculates that fossil fuel consumption must decline by 6% each year, starting now and the IEA rules out investments in new oil and gas fields. This is why TPI’s conclusion is wrong: a company planning to, one day, reach a low level of emissions does not mean it is aligned with a global warming limit of 1.5°C. In fact, each year in which a company’s emissions are above the pathway target further compromises our planet’s ability to recover.

The case of TotalEnergies and RWE

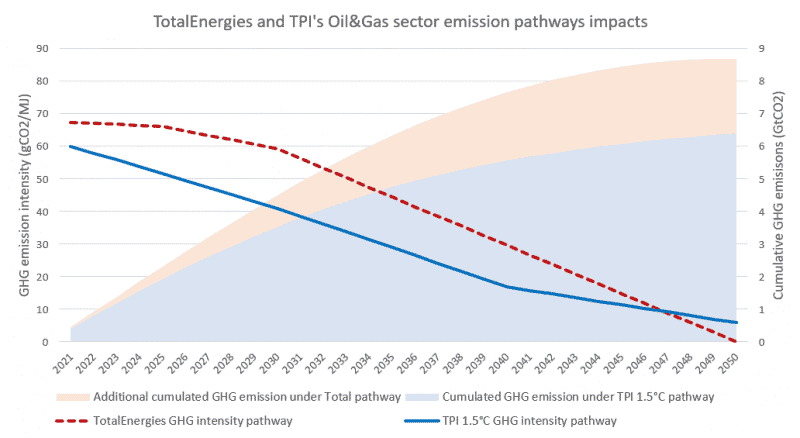

TotalEnergies is an interesting example. The oil and gas major is credited as 1.5°C-aligned because the company reaches TPI’s emission intensity target in… 2047. Each year before that, TotalEnergies is above TPI’s pathway, thus emitting too much GHG in the atmosphere and contributing to the overshoot of our short-term carbon budget. By 2035, TotalEnergies’ emissions under its own scenario will already be more than 33% higher than if it aligned from now on with the 1.5°C pathway provided by the TPI. By then, even if TotalEnergies tried to drastically reduce emissions, it would be too late to avoid irreversible climate impacts.

This graph shows how TotalEnergies is not aligned with TPI’s 1.5°C pathway, but only says it intends to achieve the levels of emissions prescribed from 2047 going forward (2).

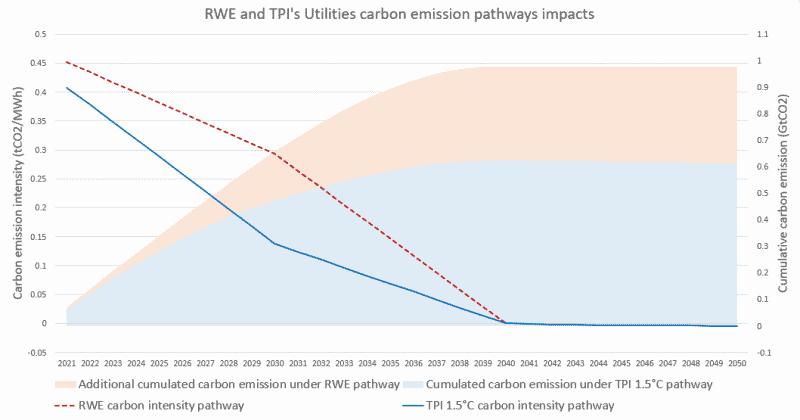

Similarly, European giant utility RWE’s emissions are consistently higher than TPI’s pathway until 2040. However, the TPI credits RWE as being aligned with its 1.5°C pathway merely because in the year 2040, RWE targets meet the pathway’s emission intensity. This means that for the next 20 years, RWE emission intensity will be consistently higher than the pathway’s targets: hence, RWE will emit in the short term and under any scenario a significantly higher quantity of carbon than allowed by climate science (3).

The benchmark is a misleading tool for investors. As it stands, the TPI benchmark must not be used as a guide for investment decisions by investors who seriously want to align their portfolios with 1.5°C. Investors looking to support companies with credible climate goals have more relevant facts and metrics at hand: does the company plan to exit fossil fuels and by when? Are they still investing in new oil and gas fields, developing further LNG infrastructure, or increasing the share of unconventional oil and gas in their energy mix? Are coal companies reducing their coal power/mining production, and planning to shut down their coal assets by 2030/2040 ? They provide more tangible and concrete indicators of whether a company is following a credible transition plan.