In 2019, Crédit Agricole became the first major bank in the world to exclude coal developers and to request an exit plan from the sector from its coal clients. But three years later, new financial data reveals that the bank has failed to properly enforce its policy. Despite its commitments, Crédit Agricole has continued to finance companies, such as Glencore and Marubeni, despite their coal mines and coal power plant developments around the world. This analysis reveals the need for the French government and regulators to monitor the concrete application of the policies adopted by the financial institutions, and apply sanctions in case of policy breaches.

Crédit Agricole, a pioneer bank on coal

In June 2019, Crédit Agricole became the first international bank to adopt a climate strategy worthy of the name, with pioneering restrictions on the coal industry. Crédit Agricole was the first major financial institution to address coal expansion, as well as require its clients to plan for a full coal phase out.

”The Group also undertakes to stop working with corporations currently developing or planning to develop new thermal coal capacities along the entire value chain (mining, production, utilities, and transport infrastructures).” Press release, June 13th, 2019 (in French)

NGOs across the world welcomed this policy, which has since become best practice at international level. But 2022 is time for a reality check: two years after the announcement of this policy, an in-depth scrutiny of Crédit Agricole transactions (1) shows that several of them are clearly in violation of the policy: Credit Agricole has recently funded several companies which do not have a coal exit plan in line with the bank’s criteria and are still developing new coal plans.

What did Crédit Agricole commit to exactly?

A year after announcing its climate strategy, Credit Agricole adopted sectoral coal policies detailing new restrictions by its corporate and investment banking activity in three sub-sectors: mining, power, and transport infrastructure.

The policies detailed the phased implementation of the restrictions and provided for a “transitional phased approach over the period 2020-2021” for coal developers already in the bank’s portfolio:

- starting in 2020, a close monitoring and analysis of each client’s direction of travel. If the analysis didn’t give enough evidence, the company was placed on a watchlist.

- from 2021 onwards, the clients were all explicitly requested to adopt a coal phase-out plan, including the end of any further coal developments.

“For the continuation of financial services from 2021, the Bank expects its clients to develop and communicate to it an phasing out plan in line with the timetable recommended by climate science (2030 for EU and OECD countries and 2040 for the rest of the world), including a commitment not to develop new projects”. Crédit Agricole sector policy, March 2020

How did Crédit Agricole breach its coal policy

Our analysis reveals that in 2021, Credit Agricole financially supported a number of coal developers, in clear violation of the criteria set out in its policies. For instance:

- Glencore : Glencore still plans an expansion of 45Mt of coal per annum in 9 mines in Australia and South Africa, making it the 9th largest coal mine developer in the world. Despite this, Crédit Agricole participated in February 2021 in a bond issue of over €1 billion and in March 2021 a general loan of over $4.5 billion to the Swiss mining giant. Furthermore, Glencore, a company that claims to be on a transition path, does not plan to close its coal mines ahead of their due closure date, and plans to continue producing coal until after 2050.

- Marubeni: Marubeni is still involved in the construction of 3 new coal-fired power plants, Nghi Son 2 in Vietnam, Cirebon 2 in Indonesia and Tokuyama East (TKE3) in Japan, for a total of 2,620 MW. Despite these well-known plans, Crédit Agricole has contributed in February 2021 to a loan of more than 500 million dollars to the Japanese giant. Ironically, Crédit Agricole withdrew from direct financing of the Cirebon 2 plant at the beginning of 2017, but continues to indirectly finance Marubeni four years later. If the Japanese trading house has committed to phasing out coal by 2050, this exit is 10 to 20 years too late compared with what climate science and Crédit Agricole require.

- Itochu: the Japanese coal company is involved in the highly controversial 2,000 MW coal-fired power plant project in Batang, Indonesia. Nevertheless, Crédit Agricole contributed a general loan of $500 million to Itochu in June 2021. Itochu has announced its exit from the coal sector by 2024 but the commitment does not include coal power plants, only coal mines. To make things worse, Itochu is only planning to sell its coal mine assets, instead of closing them.

- En+/Rusal: This Russian aluminum producer is planning to increase coal production by 35 million tons per annum, in five coal mines in Russia. Yet, Crédit Agricole participated in a general loan of $200 million in January 2021 (2).

When asked to comment on these problematic transactions, the bank told Reclaim Finance that it considered them in line with its policy and that it was “in constant dialogue with these customers to explain Crédit Agricole’s expectations and regularly discuss their climate strategy”. It indicates that the transitional phase for coal developers ended on December 31st, 2021, and therefore that its explicit request to companies to adopt an exit plan from the sector including the cessation of development “from 2021” “for the continuation of financial services” had to be understood… “from 2022”!

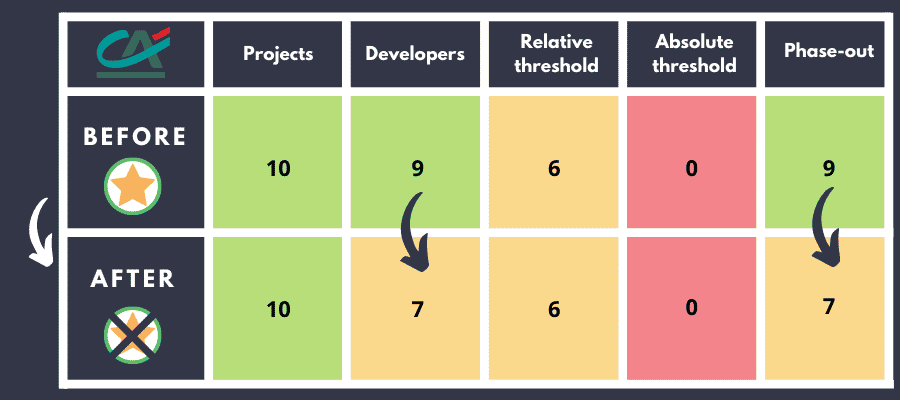

However, the fact that all these companies have in no way given up on these coal sector development projects, and that their exit strategy is still far from the imperatives dictated by climate science and by the bank’s own policy, should have been enough to place them in 2020 on the bank’s watchlist, “limiting the financial services made available to them to the financing of, and investment in, energy transition”. Given this did not happen, Reclaim Finance has therefore decided to revise the rating of Crédit Agricole CIB’s policy in the Coal Policy Tool. Crédit Agricole lost several points and its ‘star’ which qualified its coal policy as ‘robust’.

This table presents the coal scores of Crédit Agricole based on five criteria of the Coal Policy Tool.

The urgent need for compliance and sanction mechanisms

This first scrutiny exercise raises a much broader and deeper issue: that of compliance mechanisms for all the financial institutions who have voluntarily adopted coal policies (3). Reclaim Finance will monitor the application of the coal policies of the other major French and then international financial players in the coming months. Whether Crédit Agricole’s violations are unique or just the tip of the iceberg, they underscore the need for regulation and sanction. In 2018, French Finance Minister Bruno Le Maire announced at Climate Finance Day 2018 that he would force banks to exit coal if they did not actually do so.

“In the coming weeks, therefore, I will bring together banks, insurers and asset managers to make new commitments [and] to definitively stop financing the activities most harmful to global warming, in particular coal. […]. The commitments must be precise, the commitments must be monitored and if ever these commitments, on a voluntary basis, defined together, are not respected, they will be made binding”. Bruno Le Maire, Climate Finance Day 2018

Three years later, it has become very clear that it is dangerous to rely solely on financial players’ good faith to adapt their policies and align with the international objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. Reclaim Finance calls on the French government and presidential candidates to commit to regulating the practices of financial actors. In particular, the State must prohibit the financing of certain activities, ensure verification of the application of voluntary policies and sanction policy breaches.