The Glasgow Financial Alliance on Net Zero has issued a draft paper (1) that proposes a new “Expected Emission Reductions” (EER) methodology for measuring financial institutions’ contributions to decarbonizing the economy. GFANZ argues that current approaches to financial sector decarbonization incentivize divestment from high-emission companies, while what is needed, GFANZ claims, is for these companies to be provided with more financing to assist their transition. Reclaim Finance has submitted comments on the paper to GFANZ which have been endorsed by eight other NGOs. The comments warn that while the current approaches to decarbonization pushed by GFANZ and its member alliances need to be greatly improved, the EER approach is fatally flawed, and risks being used to justify continued high levels of finance for fossil fuel companies without putting any meaningful pressure on them to change.

The GFANZ consultation paper proposes a new future-focused methodology to measure financial institutions’ efforts to decarbonize the finance sector. This EER methodology would reward financial institutions based on the projected volume of emissions that would be avoided due to their investees’ and clients’ transition plans. GFANZ argues that current approaches incentivize financial institutions to divest from carbon-intensive companies (2). Yet what is needed to reduce “real-world emissions,” GFANZ claims, is for carbon-intensive companies to be provided with more capital and financial services to enable them to invest in their transition.

EER: an offsets-style metric that is complex, subjective and easily gamed

EER would be generated based on the gap between a counterfactual baseline of supposed “business-as-usual” emissions for a company or sector which fails to transition, and the projected emissions pathway where its transition plan is successfully implemented. These guesstimates would require a complex, inevitably opaque and easily gamed set of subjective assumptions on factors such as energy demand, economic growth, corporate performance, and legal, regulatory, political and social changes, over many years, potentially decades. This reliance on subjective counterfactuals parallels the conceptual foundation of carbon offsets — and is a key reason why that market is beset with scandals and suffers a profound crisis of legitimacy (3).

An implicit recognition that engagement must be strengthened

The proposed EER methodology would encourage increasing finance to fossil fuel companies and other major polluters, with no guarantees of robust engagement processes to ensure the implementation of credible transition plans.

Engagement with polluters is currently a key part of the recommendations and guidelines of GFANZ and its alliances. But if GFANZ is now saying that current approaches are leading to divestment and not reducing emissions, this is an implicit admission that their current engagement practices are not working to bring down their clients’/investees’ emissions. The logical conclusion to draw from this would be that engagement practices need to be strengthened, but there are no suggestions in this paper on how to do this (or even a recognition that it is necessary).

Rewarding big polluters with big money

Fossil fuel companies are currently awash with cash and, as numerous studies have shown, are making at best a mostly performative effort to transition to clean energy (4). It is simply not credible to claim that pushing these companies to transition out of oil, gas and coal requires not only continuing to provide them with huge amounts of loans, investments and financial services, but to offer them even more.

Transition finance is needed, EER is not

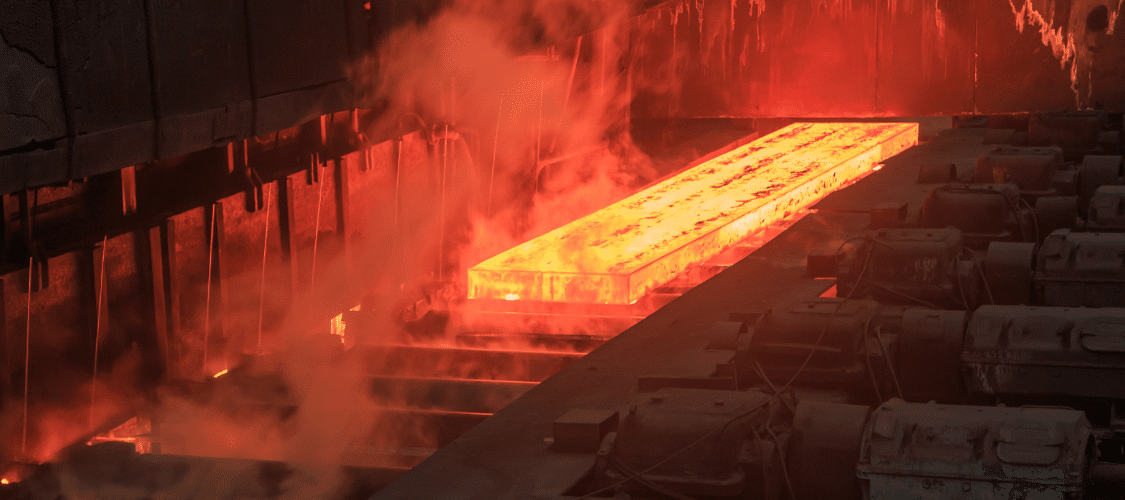

For some currently highly carbon-intensive industries, such as cement, steel and aluminum, their products cannot easily be substituted and will continue to be needed in high volumes. In these cases, transition finance is needed, but the paper fails to make the case that the EER concept would specifically be an effective tool to speeding up the decarbonization of these “harder-to-abate” sectors (5). The paper also fails to make any differentiation between how financial institutions should treat sectors which need to change their production processes, and those like fossil fuels that need to be phased out.

GFANZ implies that providing finance to companies that are committed to decarbonizing in harder-to-abate sectors would lead to increases in financed emissions across a bank’s or investor’s portfolio, and that these increases in financed emissions would be sufficiently large and sustained that they would dissuade the financial institution from doing these transactions. However they provide no calculations that model the impact on their overall financed emissions from likely transition finance deals, and so fail to prove that this is indeed a significant problem.

Phaseout finance

There may be cases where increased financing for fossil fuel companies or projects can be justified, for example where finance enables phaseouts of coal plants, and where the amounts of this finance would be so large that it would have a significant impact on a bank’s or investor’s total financed emissions. In these cases, the finance can be ringfenced as “phaseout finance” provided it is accompanied with robust environmental and social safeguards, including that its recipients are not building new fossil fuel plants.

Avoiding critiques of avoided emissions

In addition to pushing EER to incentivize funding for high-carbon companies, the paper recommends that an “avoided emissions” approach should be used for evaluating the impact of financing for climate solutions. This approach has been used in the past by renewables developers, and their financiers. But it has come under strong criticism and has mostly been dropped, including because of the problem of exaggerated baselines (6).

Approaches to aligning finance with 1.5°C that focus only or mainly on financed emission targets are indeed inadequate to aligning the real world with 1.5°C. But the answer to the flaws and lack of ambition of finance sector decarbonization targets is to improve their design, level of ambition, and implementation (7). It is also imperative that decarbonization targets be just one part of financial institution net-zero transition plans. While GFANZ says the EER methodology would “complement” current approaches, there is a risk that it would become a core “transition” metric for financial institutions and might also be taken up by financial regulators.

Key elements of credible transition plans have been outlined by the UN High-Level Expert Group on net zero (HLEG), and must include effective engagement, exclusion and voting criteria, and an end to finance for fossil fuel expansion. GFANZ needs to grasp the nettle of the fact that a commitment to net zero requires its members to be prepared to break sometimes decades-long and until now very profitable relationships with some key clients and investees, and to stop clutching at the straw of believing that accounting tricks can achieve real-world decarbonization.