In early February, Barclays published its revised oil and gas policy alongside its Transition Finance Framework [1]. What may seem at first glance to show a keen understanding of the urgent need to move away from fossil fuels (while at the same time developing the energies and technologies to limit warming to 1.5°C), turns out to be disappointing after reading in full. Indeed, what is striking about Barclays’ oil and gas policy is the number of references to oil and gas expansion , and the absence of firm measures to cease funding it. The Transition Finance Framework does not increase the bank’s commitment to support the energy transition. In fact, it dilutes the bank’s previous commitments, which were already inadequate in terms of achieving a rapid and just energy transition.

Barclays replicates the policy loopholes seen at its European peers

While Barclays says it will no longer provide project finance for new oil and gas fields, this progressive step forward could actually be meaningless. Like most banks, Barclays’ support for the oil and gas industry is mostly channeled through corporate finance, with only 7 transactions dedicated to oil and gas production since May 2021 but none for new fields [2].

Barclays also commits to ending project finance for “infrastructure projects primarily to be used for such [upstream] expansion projects”. Similar restrictions have already been adopted by other European banks, namely HSBC, ING, and Société Générale [3] and falls short of what is needed to align with the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) net zero pathway [4]. This says that no new gas liquefaction terminals are needed to meet future demand. By copying its peers instead of following science, the British bank risks going against its own stated objectives [5] and supporting the development of more gas fields, as any new LNG infrastructure would facilitate market access for their production.

No systematic sanctions against oil and gas companies

The bank does announce some measures regarding oil and gas companies, but these are feeble, as they allow Barclays to continue supporting the very same companies that are responsible for developing more than 73% of expected new oil and gas fields [6]. All of these measures should have little to no impact on Barclays’ best clients, including ExxonMobil and Shell, with Barclays providing more than US$12.997 billion to ExxonMobil and US$6.736 billion to Shell between 2016 and 2022 [7].

The policy says that “non-diversified Groups where more than 10% of their total planned oil & gas capital expenditure is in long-lead expansion” could be excluded from January 2025 [8]. In other words, even upstream companies, which account for 26.3% of expected new oil and gas fields [9], would not automatically be excluded from all new financial services. This may even be weaker than the policies seen at other European banks [10], like Crédit Agricole. Indeed, Crédit Agricole excluded all independent oil and gas producers, which account for 19.6% of the expected oil and gas fields, and this exclusion did not allow for any exception.

The policy also introduces a requirement that all energy companies adopt “transition plans” which consider a number of factors, including not expanding oil and gas upstream production. However, non-compliance with this criterion does not trigger exclusion. In fact, other criteria, which could guarantee the reduction of the company’s absolute emissions, are not part of the minimum requirements to be met by the end 2025 [11].

Energy transition: no steps forward, two steps back

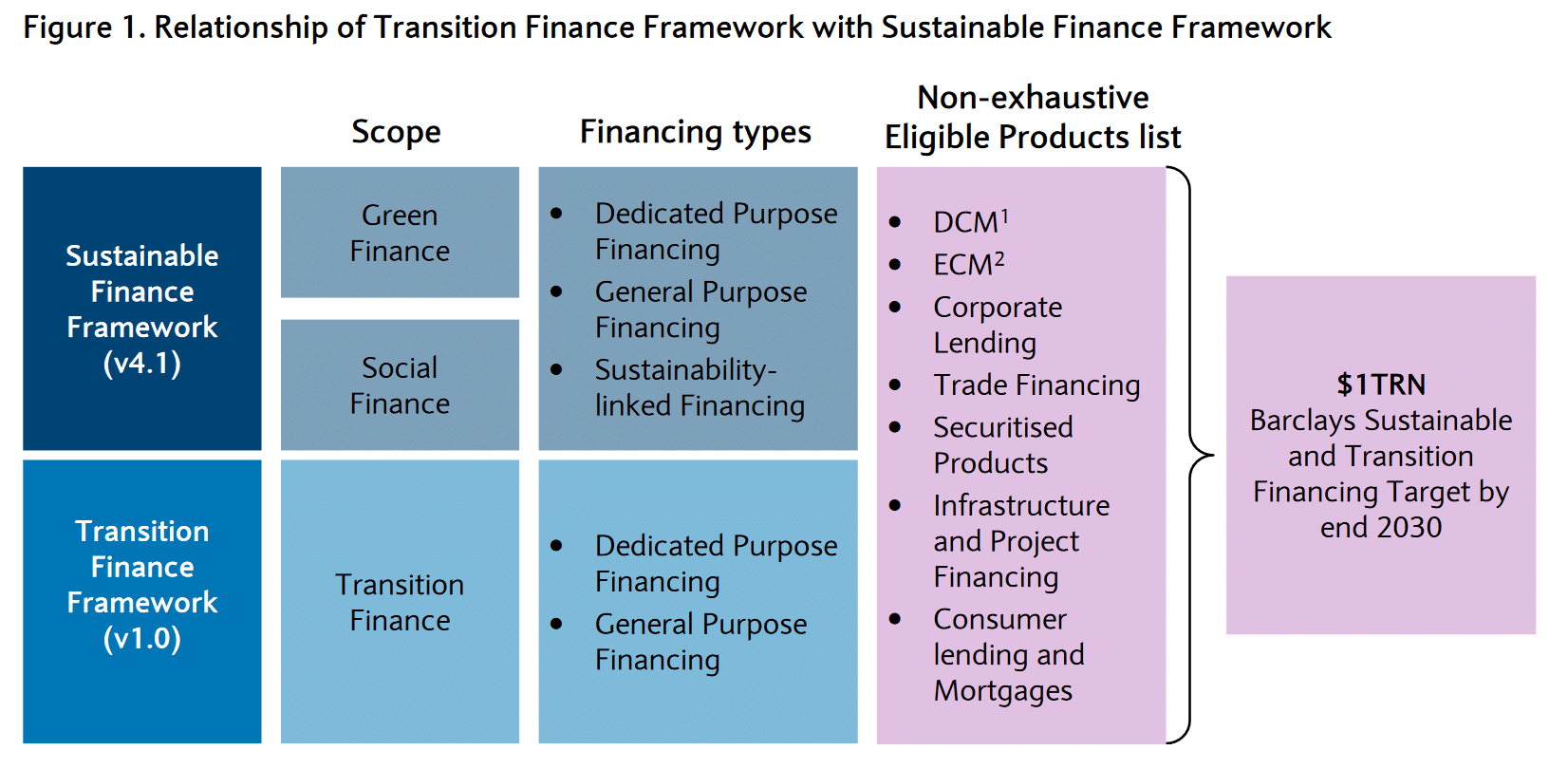

Barclays’ announcement also concerns support for the development of alternatives to fossil fuels. This aspect is a subcomponent of both its “Sustainable Finance Framework” [12], published in December 2022, and its new “Transition Finance Framework” [13]. Barclays’ new framework risks undermining the already vague objective which was announced in 2022 and which aimed to secure US$1 trillion of financing for activities, initially identified by the bank in the first framework. Two issues might be raised.

First, while aligning with climate science requires banks to adopt specific financing targets for key sectors, and in particular for the power sector, Barclays is doing the opposite. It was already impossible to assess the impact of Barclays’ US$1 trillion financing target announced in December 2022 as the related “Sustainable Finance Framework” covered such a vast range of sectors and activities. This new framework expands the scope of sectors and activities covered by the bank’s financial target even further, waters it down even more. In other words, this could result in less financing for sustainable energy and for the technologies that need to be urgently developed.

Secondly, the new “Transition Finance” Framework includes technologies which could impede a just transition out of fossil fuels. This is particularly the case of hydrogen produced from fossil fuels (so-called “blue” hydrogen) which would only increase our reliance on fossil fuels. Also, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), which is still unproven to be deployable at scale, is mostly put forward by fossil fuels proponents to delay their phase out. Such technologies have no place in financing that is labeled as sustainable or as transition [14].

This announcement is therefore a bad omen at a time when it’s urgent for banks to scale up their efforts and adopt specific financial targets for sustainable power supply. Instead of adding layers to vague commitments, Barclays should adopt a specific financial target for energy supply and focus such financing on sustainable sources and technologies that are mature, rapid to deploy and have less impact on ecosystems and human rights: wind and solar, upgrading electric grids and power storage.

Source : Barclays Transition Finance Framework 2024.

Barclays missed the opportunity to align its climate strategy with climate science, requiring both a halt to oil and gas expansion and a massive development of sustainable energy sources and technologies to replace fossil fuels. Reclaim Finance calls Barclays to immediately and systemically exclude companies with oil and gas expansion plans, without exceptions. At the same time, Barclays must adopt a specific financial target focused on sustainable power supply, excluding false solutions, and commit to a financing ratio of 6:1 by 2030 [15].