On September 30, 2024, the United Kingdom officially became the first G7 country to phase out coal power. With the shutdown of its last coal plant, Ratcliffe-on-Soar, the UK reached its target one year ahead of schedule, marking a significant milestone in the energy transition of this former coal powerhouse. Unfortunately, UK financial institutions have not gotten the message on the coal phaseout imperative and are continuing to provide finance to sustain the coal industry globally. Policymakers and regulators in the UK and elsewhere need to step in to ensure that domestic policies to phaseout coal are not undermined by financial institution practices.

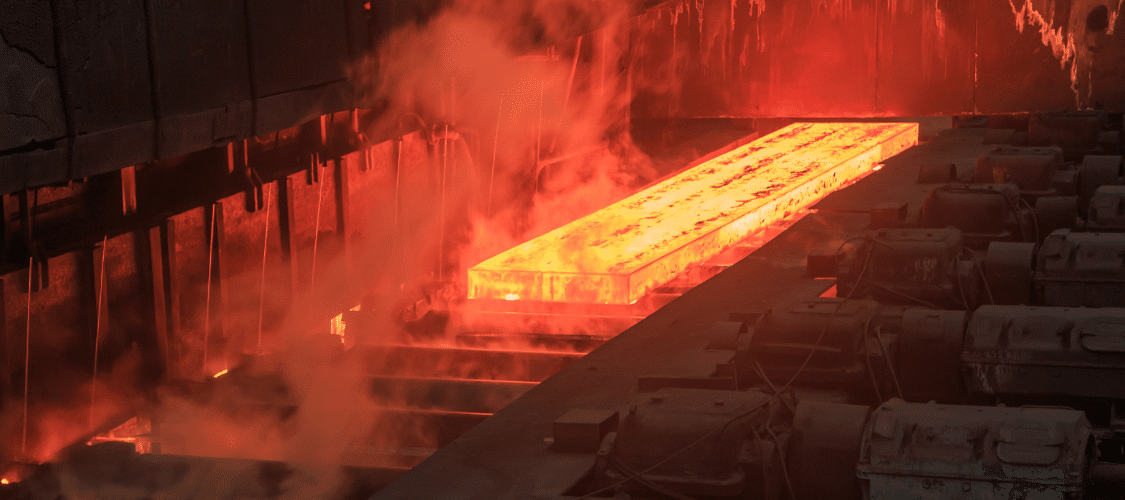

Coal was once king in the UK. It powered its industrial revolution and later its electrical grid. At its peak, coal accounted for over 70% of the UK’s electricity generation, with thousands of mines operating across the country and over a million people employed in the sector. Less than 30 years ago, coal still provided around 40% of the UK’s electricity, but now the country leads the charge in phasing out coal.

The rapid phase out of coal power from the UK’s grid over the past decade is due to forward-thinking climate policies, a clear regulatory framework, and the rise of wind power, even though coal production has been declining in the UK for over a century. By investing in renewable energy, the government created affordable and accessible alternatives to coal, while also improving grid infrastructure and management and signaling the full costs of coal through effective carbon pricing. (1) These measures helped push coal out of the market, paving the way for renewables to replace coal.

A lagging global coal transition

Unfortunately, beyond the UK, the global picture is less optimistic. In 2023, the world saw the lowest number of coal plant retirements in over a decade. Currently, only 15% of global coal capacity is on track for closure in line with the 1.5°C goal. (2) Without a concerted, international push, the world will not achieve an end to coal in OECD/Europe by 2030 and worldwide by 2040.

In the US, it is uncertain if the formerly rapid rate of coal retirements can be maintained. The country’s coal lobby is claiming that plants must be kept open due to the possibility of sharp increases in electricity demand to power the servers that process data for AI. (3) In Japan, South Korea and elsewhere, the necessary switch from coal to renewables is being slowed by the promotion of false fixes, such as LNG, carbon capture and storage (CCS) and co-firing coal with ammonia, hydrogen or biomass. (4)

Time for private finance to follow suit

The private finance sector in the UK is unfortunately profiting from the continued life of the coal industry overseas and has not kept pace with the government’s forward-looking coal phaseout. Between 2021 and 2023, UK banks contributed US$6.5 billion to the global coal industry. UK banks rank seventh in the world for funding coal, with Barclays the biggest European banker of coal expansion. Barclays continues to back companies such as Adani Group and Glencore, which are still expanding their coal operations. In fact, Glencore recently rolled back its plans to phase out its coal business because of its remaining profitability. (5)

Unfortunately, UK banks are not the only one still funding the expansion of coal. Globally, commercial banks provided US$470 billion to the coal industry between 2021 and 2023 – money that could have otherwise been channeled into sustainable energy investments, grid infrastructure improvements, and energy efficiency. (6) Among G7 members, US and Japanese banks are the top lenders to the coal industry. Japan, the only G7 country without a coal phaseout plan or a specific end date for coal power, is home to banks that have dominated international coal lending and bond facilitation from 2021-23, including Mizuho ($8.1 billion), MUFG ($6.1 billion) and SMBC ($4.7 billion).

Redirecting finance towards coal phaseouts and sustainable investments

The disconnect between government policies and private finance shows the urgent need for financial regulations that require banks to stop supporting coal other than for the early decommissioning of coal assets, and to shift financing to sustainable investments.

The UK’s coal phaseout proves that progress is not only possible but achievable with the right policy mix. However, this domestic success is being undermined by UK financial institutions that continue to fund coal expansion overseas. Policymakers and regulators must urgently address this disconnect by implementing stronger financial regulations that compel private finance to end support for coal expansion, except for projects related to early coal plant decommissioning. The UK has shown that good policy works, but it cannot be the exception. It’s time for other countries — particularly rich economies like the G7 — to follow suit by adopting clear coal phaseout timelines and redirecting investments away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy and coal retirements.