Public finance will be at the heart of the discussions at the upcoming COP29 in Baku. On the agenda is the new target for climate finance for developing countries that developed countries are expected to commit to. Private finance will also be on the table, in particular to help pay for sustainable energy and phasing out fossil fuel infrastructure in the Global South. Reclaim Finance believes that private finance has a role to play given the enormous financing needs, but it must complement rather than replace public concessional financing. For mitigation investments that have the potential to be profitable, governments and public banks must provide risk mitigation mechanisms and other incentives to attract private capital. But private banks and investors should not benefit from public subsidies intended to reduce emissions while they are continuing to finance the expansion of fossil fuels.

Governments are supposed to agree in Baku at what has been dubbed the “finance COP” on a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) for North-South climate finance. The target is to cover mitigation and adaptation costs, which were covered under the previous US$100 billion annual target set in Copenhagen in 2009. It is still to be decided if funds for loss and damage for climate impacts in developing countries should be provided in addition to the NCQC. (1)

The lower bound of estimates for the NCQG is an entire order of magnitude higher than the Copenhagen target. This estimate of at least a trillion dollars is certainly much closer to the real need than the previous goal. (2) Climate Action Network and others have shown that mobilizing a trillion dollars a year in grants and grant-equivalent finance is achievable. This can be done by diverting public funds from subsidizing fossil fuels and other harmful activities, making rich polluters and profiteers pay, and reforming inequitable international finance rules. (3)

Not climate finance: private finance, offsets and gelato

Securing trillions of dollars in North-South finance will undoubtedly be a significant challenge. The US$100 billion target was finally met in 2022, according to the OECD, but only because of including under the definition of “climate finance” not only grants, but also non-concessional public loans and guarantees as well as private loans and equity investments. (4) OECD members also included a bewildering array of activities under their classification of climate finance, including Italian gelato parlors in Asia and a Japanese-funded coal plant in Egypt. (5)

A concern regarding the NCQG is that it may also allow developed countries to meet their obligations by setting their own definitions of what constitutes climate finance, and that this will include private finance, and offsets. The NCGC must be met with grant and grant-equivalents from the public sector. Private finance must be considered supplemental to the NCQG for reasons including that private finance will always focus on profitable projects, and so will mostly bypass the poorest communities and fail to support adaptation projects that will not generate cash returns. Moreover, private finance and non-concessional loans will add to the debt burdens of highly indebted countries.

If countries finally agree on the rules for the seriously flawed Article 6 carbon offsetting schemes, whether in Baku or later, there is a risk that massive purchases of highly questionable offsets by governments and corporations will be considered as part of NCQG commitments. (6)

The other finance COP

COP26 in Glasgow was also called a “finance COP” due to its emphasis on private finance. The private finance sector has an important role in meeting the goals agreed last year in Dubai of tripling renewable energy deployment and doubling energy efficiency. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), investment for renewable power, grids and storage, and energy efficiency and electrification, rose from US$1.4 billion in 2021 to a projected US$2 billion in 2024, with about 75% of this investment coming from private sources. To meet the Dubai targets the IEA estimates the current level of clean energy investment worldwide will need to double by 2030. (7)

The Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ) garnered significant media attention at COP26 for its announcement that its 450 banks and investor members — comprising many of the giants of global finance — were committing their joint assets of $130 trillion to climate action. (8) The headline number was misleading as it represented the sum of GFANZ members’ total assets rather than specific funds earmarked for net-zero activities (9) Nevertheless, this figure underscores that while the estimated need for at least a trillion dollars for the NCQG may seem high, it is relatively small compared to the overall size of the global economy.

A primary objective of GFANZ is “to mobilise capital for decarbonisation in emerging markets.” (10) Evidence suggests that GFANZ has much more work to do here as only around 15% of clean energy investment in 2024 is expected to flow to developing countries outside of China. The IEA states that investments in clean energy in these countries must quadruple by 2030. (11) While most clean energy investment in the poorest countries will need to come from public sources, private finance is still important in supporting the energy transition in developing countries, but it will need to be backed up by the public sector through guarantees, differential interest rates and other derisking mechanisms.

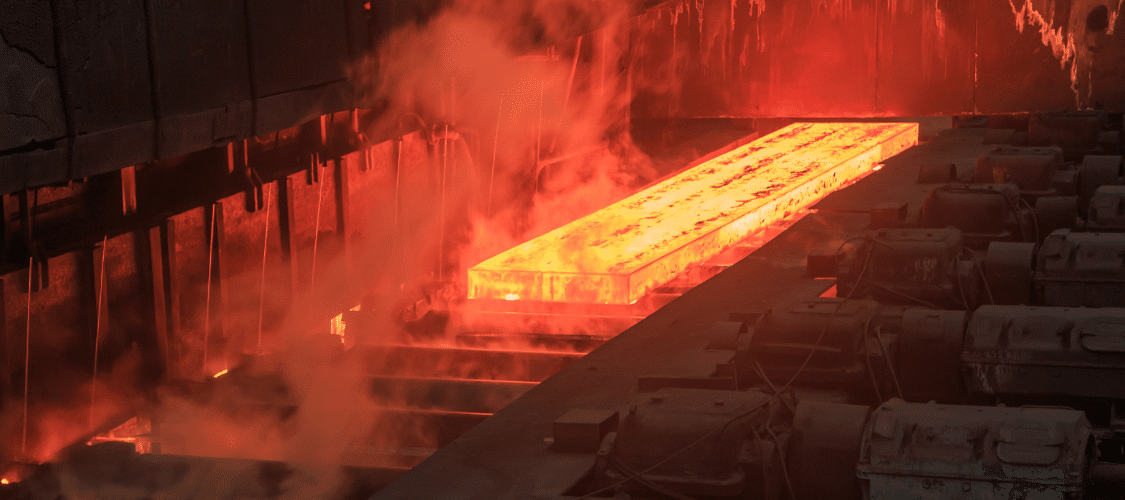

Financing fossil fuel expansion risks economic disruption

While investment in clean energy is rising, so is investment in fossil fuels, with 20% increases for coal and oil since 2021 and a 29% increase for gas. (12) This influx of capital is supporting new projects which could lock-in emissions for decades. This trend is not surprising given that only a handful of GFANZ members have adopted policies to restrict their support for new fossil fuel projects. (13) Most GFANZ members have focused on meeting their net-zero commitments with decarbonization targets. Reclaim Finance’s detailed analysis of the decarbonization targets of 30 members of the Net-Zero Banking Alliance, however, shows that these targets suffer from serious methodological problems making them unlikely to result in meaningful reductions in real-world emission. (14)

GFANZ’s reluctance to confront the issue of fossil fuels means that achieving the Dubai goal of transitioning away from fossil fuels “in an orderly and equitable manner” will require government action. The longer banks and investors continue to support new fossil fuels, the more disorderly and disruptive the transition is likely to be. (15) Regulations are needed that compel financial actors to cease all support for fossil fuel expansion and direct finance toward sectors that have the potential to transition (16) — provided that the beneficiary companies have robust transition plans in place. (17)

Chasing the carbon chimera of offsets

Considerable excitement was generated at Glasgow by the announcement of the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) to close South African coal plants. This optimism, however, has faded in the face of an institutional crisis in the country’s huge power utility, the unwillingness of donors to provide significant funds at concessional rates, and private banks’ and investors’ aversion to financing projects with no clear prospects of being repaid. (18) Other JETPs for Indonesia and Vietnam, announced soon after South Africa’s, have also stalled for broadly similar reasons. (19)

The difficulties in finding funding for coal phaseouts has led private sector actors, including GFANZ and some of its members, to try to establish an offset mechanism to help pay for coal phaseouts in Asia. But offset schemes have a notorious history of fraud (20) and have consistently failed to deliver the promised economic benefits for developing countries. (21) Even if these schemes result in real emission reductions from the early closure of coal plants, the climate benefit may be negated as offset buyers can use them to evade cutting their own emissions. (22)

Private finance should leave this second finance COP with a strong commitment to step up its game on net zero: adopting policies to stop financing fossil fuel expansion and targets to rapidly ramp down financing for any fossil fuel companies that are not in the process of implementing meaningful 1.5°C transition plans. Meanwhile governments need to leave Baku with an agreement for a NCQC that is large enough to meet the scale of the crisis and will be funded with grant-equivalent finance. And beyond Baku, governments need to put in place regulations to ensure that private finance sector stops undermining climate goals with continued support for new coal, oil and gas projects.