Decarbonize steelmaking

Financial institutions must end steelmaking’s reliance on coal

Limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires ending the world’s reliance on fossil fuels. Achieving this challenge will only be possible through the adoption of comprehensive approaches that tackle fossil fuel production while simultaneously addressing demand-side sectors that consume fossil fuels themselves, such as the steel sector.

Current ways of producing steel are heavily carbon-intensive due to their reliance on coal – also called metallurgical coal (met coal), which refers to all grades of coal – like coal for pulverised coal injections (PCI) and coking coal – used in steelmaking. Decarbonizing steelmaking while meeting demand with cleaner and competitive alternatives is possible and must become a priority.

The decarbonization of steel production will only be possible if financial institutions step up to finance the right solutions. They must urgently refuse to perpetuate the steel sector’s reliance on coal and finance cleaner technologies instead.

Debunking 10 steel decarbonization myths

Insights for financial institutions

The steel industry, long considered “hard-to-abate” due to its reliance on metallurgical coal, can now decarbonize faster thanks to technological advances. However, financial institutions remain slow to act, hindered by misconceptions about the cost and feasibility of decarbonization. Steel accounts for 11% of global CO2 emissions, and with demand expected to rise and aging facilities, the next six years are crucial for transforming production. The goal of this briefing is to dispel the common myths that financial institutions hold about steel decarbonization and the role of metallurgical coal.

Steel, a key component of our societies

From buildings, to cars, to domestic appliances and other equipment, steel is virtually omnipresent in our modern world, and it will not go away anytime soon. Projections predict that steel demand will increase, driven in part by developing and emerging economies that need more steel as they industrialize. Steel is also an essential part of the energy transition as it is used to build infrastructure and products such as wind turbines, solar panels, and electric vehicles.

Projections show that steel production could increase by a third by 2050. Many current steel facilities are also nearing the end of their lifetime, meaning they will need to be refurbished by 2030. With major investment needed, this is an opportunity to shift to cleaner technologies to produce steel. Getting it wrong would be fatal as it would mean the development of coal-based capacity, which, with a lifetime of around 20 years, would lock in emissions for decades, ruining any hope of decarbonizing the steel sector in time to reach net zero by 2050.

“The current pipeline of projects clearly nonetheless falls short of what is required to meet the Net Zero Scenario.” International Energy Agency, 2023

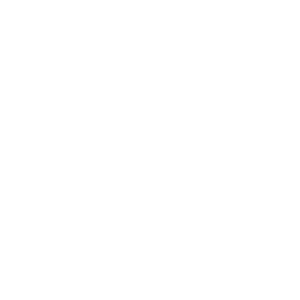

How steel is made

Today, there are two main ways to produce steel. Most of the emissions from steel come from manufacturing steel from raw materials, using metallurgical coal and iron ore. This is known as primary steelmaking. It is for the most part done using the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace route (BF-BOF) and accounts for almost 70% of global steel production, making it responsible for 90% of the steel sector’s total CO2 emissions.

Steel can also be produced by recycling scraps of steel. This is known as secondary steelmaking, and uses electric arc furnaces (EAF). This route is seven times less carbon-intensive than primary steelmaking, and even more so if it runs on clean sources of electricity, but it is highly dependent on scrap availability and quantity.

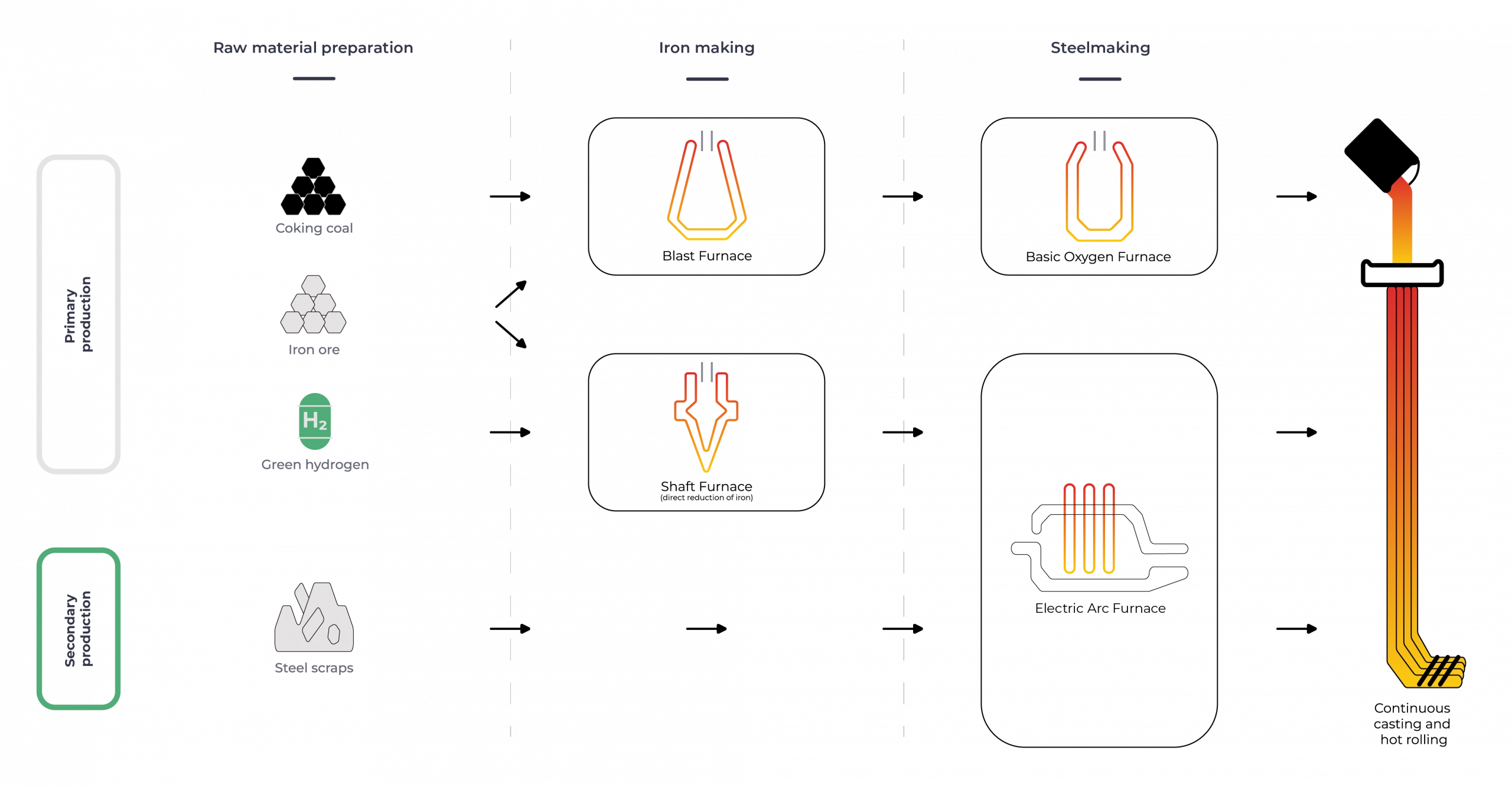

Less carbon-intensive ways of producing steel exist or are in development. Recent technological advances, especially using green hydrogen to reduce the iron (Direct Reduction of Iron, DRI), make it possible to entirely rid the steel sector of coal by the mid-2040s. This implies that green hydrogen must be prioritised for so-called “hard-to-abate” sectors where it represents the best option for decarbonization. Increasing the availability of sustainable power sources for steel facilities is also key to decarbonizing the sector.

Decarbonizing steel: time is of the essence

of global CO2 emissions produced by steel.

Due to its reliance on coal, the steel sector produces 7% of global GHG emissions and 11% of global CO2 emissions.

Decarbonising the steel sector is key to keep the 1.5°C target within reach. The International Energy Agency’s Net Zero Scenario calls for steel sector emissions to drop by 25% by 2030 and almost 92% by 2050. To achieve this, metallurgical coal production would need to fall by about 30% by 2030, and by 88% by 2050, based on 2021 levels. This implies that a 100-fold increase in production using cleaner steelmaking technologies would need to happen by 2030.

Yet, in many parts of the world, steel projects are heading in the wrong direction. Research by Global Energy Monitor shows that although EAF-based capacity makes up 50% of all projects in development, less than a third of these projects have reached the construction phase. Coal-based production continues to dominate, with 46% of steel projects that have broken ground still BOF-based.

There is an urgent need to increase financing to develop and deploy alternative technologies that now exist. DRI continues to pick up pace, now representing 42% of projects in development, but it has still fallen short of decarbonization goals.

Steeling our future

The banks propping up coal-based steel

The iron and steel sector has a heavy climate impact, accounting for 11% of global CO2 emissions. Decarbonizing the steel sector is key to respond to the climate emergency. The climate impact of the steel sector is primarily due to its reliance on metallurgical coal for its production. Indeed, almost 90% of steel sector emissions are attributed to the coal-based route. As new technologies that do not rely on metallurgical coal develop, studies show that coal can be phased out of steelmaking in the early 2040s. This requires immediate action from banks.

ArcelorMittal – from leader to laggard

As one of the biggest steelmakers in the world, ArcelorMittal has a key role to play in decarbonizing the steel industry. However, as it stands, the company’s current climate strategy and actions fall short of what is needed to keep the 1.5°C objective alive. Since 2018, the company’s CO₂ intensity has fallen by only 5%—far below its own 2030 targets and nowhere near what’s needed to address the climate crisis. Its long-promised Climate Action Report 3 has been delayed, leaving stakeholders in the dark as it backtracks on past commitments. Despite securing 3.5 billion USD in public subsidies to decarbonize, it has yet to make a single final investment decision on any major green steel project in Europe or Canada. Since 2021, just 2.5% of the 32.6 billion USD in operating cash has gone toward decarbonisation, while 12 billion USD was spent enriching shareholders—1.3 billion USD in buybacks and 393 million USD in 2024 dividends alone—with the Mittal family retaining 44.25% control.

In addition to its constant failure to act on climate, ArcelorMittal faces criticism for the impact of its activities on human rights and populations in many countries, including Mexico, Liberia, and South Africa. This involves indigenous and tribal communities losing control over their lands, waters, and forests, while impoverished neighborhoods face ongoing pollution that damages their health and limits their livelihoods.

Financial institutions must push steelmakers towards decarbonization

The first step for financial institutions is to stop supporting any new metallurgical coal mines, expansion plans, or new coal-based steelmaking projects, expansion projects, or the relining of blast furnaces.

The second is to make new financial services to clients and investee companies conditional on a commitment to stop developing such facilities, and to engage steelmaking companies to invest in the right technologies, across all geographies.

Financial institutions increasingly voice their discontent at climate action that is limited to the supply of fossil fuels. However, they are yet to adopt policies to address demand-side sectors. Their coal policies also mostly only target thermal coal, mostly due to the false belief that there are no alternatives to metallurgical coal. Today, only 14 major financial institutions have adopted an exclusion policy for met coal, and mostly only at the project level, when almost all of the financing occurs at the corporate level. It therefore leaves the door open to finance companies carrying out the 252 metallurgical coal expansion projects currently underway – like Glencore, BHP, Mitsubishi, and AngloAmerican – which would increase global metallurgical coal production by 50%.

Financial institutions must urgently adopt policies that restrict financing for companies developing new met coal projects, and steelmakers planning new blast furnaces or the relining of existing blast furnaces – from now in developed regions, and in 2030 in developing regions. Coal is coal, it must be phased out regardless of its end use, especially considering that the line between thermal and metallurgical coal is not as clear as it seems, as records of companies selling “steelmaking coal” to be burned in power plants are emerging. Fortunately, alternative technologies now exist and can be developed and deployed if the necessary financial resources are made available. This involves financing green-hydrogen ready facilities, and supporting the development of enabling factors like sustainable power. This is an opportunity for them to back up their words with action.