COP26

IS FINANCE UP TO THE CLIMATE CHALLENGE ?

We’re on borrowed time.

From the IPCC to the IEA, no one now doubts the urgency of the climate crisis, and the rapid phase-out of fossil fuels required for 1.5°C to stay alive. Whatever the world’s governments decide at COP26, that means that private finance’s support for fossil fuels must also end. But banks, insurers and investors are still far from aligning with the demands of climate science: there are far too many weak coal policies and, astonishingly, next to no policies in place to turn off the taps for oil and gas expansion.

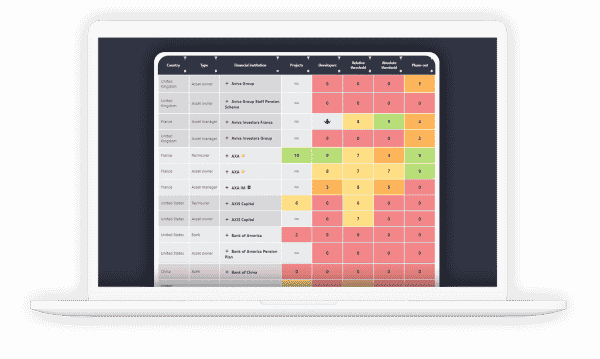

Unfortunately, the cascade of policy announcements over the past year hasn’t helped much. There are hundreds of companies developing new coal, oil and gas projects. Fancy pledges remain just that if they don’t decisively contribute to ending fossil fuel expansion now and quickly exiting coal. This is why Reclaim Finance will be tracking new announcements by some of the world’s biggest financial institutions before and during COP26. As CEOs strut onto the stage, we’ll be shining a spotlight, sifting the good from the bad, the green from the greenwashed.

As we go, we’ll watch out for the same old loopholes hiding behind net zero pledges and emission reduction targets, that prevent us from curbing both fossil fuel finance and emissions.

Financial institutions at COP 26: our reactions

With COP 26 around the corner, more and more private financial institutions are making new climate commitments. But what to make of them? How do we sort the good from the bad from the ugly? How do we make sure that they are not just dangerous distractions from key issues like fossil fuel expansion and coal, oil and gas phase out plans? In this section, we help you to navigate new policy commitments – what is a good step to quickly exit coal and/or stop fossil fuel expansion, and what is a dangerous distraction.

6 tips to identify the good, the bad and the ugly

Ahead of COP 26, many banks, investors and insurers will be announcing new climate policies. These announcements are often used as a diversion tactic, to distract from bad practices, or worse, as a way to paint themselves green – while hiding the worst.